Panjiva Research hosted our quarterly outlook webinar on July 15. This report covers the results of polls held during the event as well as addressing some of the questions posed by attendees. A link to the recording and other content can be found here and are based on our recently published Q3 Outlook reports looking at COVID-19, the U.S.-China trade war and global trade policy risks.

We opened the event with a review of the four stages of COVID-19’s impact on global supply chains including: initial supply chain disruptions; the collapse in consumer and industrial demand; the uneven reopening of manufacturing operations; and the potential for long-term supply chain reform.

The impact of COVID-19 has already taken five months to work through supply chains with recovery likely to take several more to occur. We asked attendees at the webinar: “How long will it take for supply chain activity to return to pre-pandemic levels?“. Just 6.5% of the respondents expect a complete recovery to occur in 2020, with 61.0% expecting a recovery only in 2021 with 32.5% seeing 2022 as the stable period. That represents a later recovery profile than that observed in the same poll held during Panjiva’s June 22 event.

Source: Panjiva

Q: What’s the state of global food supplies in the wake of COVID-19?

Food supply chains have remained largely intact during the pandemic, albeit with disruptions caused by manufacturers struggling to reorient to retail supplies from food service. A bigger concern was the temporary food protectionism measures being applied by a handful of countries. These, unlikely medical protectionism, have been rapidly unwound.

The bigger issue on a go-forward basis is managing the health aspects of food production. One part of that relates to production processes, particularly in the meat industry. There is also an emerging issue of stricter food inspections on behalf of the Chinese government which is restricting imports on concerns regarding the presence of SARS-COV-2 virus on packaging.

Q: Has the U.S. “learned its lesson” regarding PPE offshoring, will manufacturing return?

There is already manufacturing capacity for a wide range of personal protective equipment in the U.S. as well as stockpiles available before the crisis started. Yet, these have proven to be inadequate in terms of the ability to surge in response to a rise in demand. This raises important strategy decisions for the future that in part lie in the hands of government: who pays to maintain stockpiles; what are the right levels; should capacity payments be made; do collaborative arrangements with U.S. allies make sense?

Panjiva’s U.S. seaborne import data shows that shipments of masks only ramped up in May, with an earlier increase in supplies reliant on FEMA’s “Project Airbridge”. Shipments in the three months to April 30 were 19.8% lower than the prior three months and 10.5% below the year earlier level. There was then a surge in May and June with total imports in the two months equivalent to the prior 30 months combined. Yet, 88.8% of imports came from China, a strategic rival for the U.S.

Source: Panjiva

Q: Do you have any insight on when air cargo capacity might increase and pricing ease?

The return of air cargo capacity to prior levels will depend on (a) the willingness of airlines to return passenger flights, and hence belly-hold freight capacity, to earlier levels and / or (b) convert aircraft to full freighters rather than the “preighter” approach followed so far.

Both remain uncertain though the forthcoming earnings reporting season may provide insights, particularly from the freight forwarding sector. In the meantime it’s worth noting that air freight capacity dropped by 34.7% year over year in May, Panjiva’s analysis of IATA data shows, while demand dropped by 20.3%. That’s meant airfreight capacity utilization, a key driver of rates, reached 57.6% in May after a 10 year record of 58.0% in April.

Source: Panjiva

The remainder of the event looked at the evolution of trade policy and corporate supply chain strategy changes. We expect the U.S.-China trade war to worsen heading into the elections and asked attendees: “What are the prospects for U.S.-China relations before the U.S. general elections?” Most respondents expect a worsening of relations from here, with 42.5% expecting a worsening without policy changes and 36.8% expecting a worsening that will lead to increased tariffs or other measures. Only 5.7% expect an improvement from today’s relationships.

Source: Panjiva

Q: Are firms likely to diversify their supply chains due to the trade tensions / health risks, and will there be an impact on profitability?

Supply chain diversification always comes with additional cost to the firm from increased management complexity. Most multinationals have worked to better their procurement and sourcing organizations to more effectively manage large diversified supply chains, but moving supplies from the best source to a wider array of sources will generally lift the average cost of inputs when you account for smaller order volume and a decreasing number of suitable suppliers.

Firms with larger margins will be more resilient to this effect – e.g. Apple would have an easier time absorbing those costs than a grocer, for example. Diversified supply chains also carry increased exposure to event risk and other point in time disruptions that could cost firms in discrete incidents.

Q: Will USMCA have an impact on global supply chains?

USMCA reinforced the North American market as a block, likely reassuring firms worried about border disruptions with the United States, although political risks still exist.

Firms with higher labor components like apparel or toys may view the low cost Mexican manufacturing environment – although higher than Asia – as a more favorable alternative to overseas shipping.

Panjiva’s data shows that Mexico has so far struggled to make significant headway in terms of exports of high labor-cost products to the U.S. Shipments of toys have only increased by 9.4% in the 12 months to March 31 compared to 2016 while exports of apparel fell by 6.2% over the same period.

Firms with more premium products will find reshoring more attractive as their higher margins can absorb a higher labor cost, while politically visible firms will likely take a more balanced approach – like auto makers manufacturing in Canada, Mexico, and the U.S.

Increased trade uncertainty, weather by events such as the pandemics or potential trade spats with the E.U., Vietnam, or India will continue to make the USMCA block more attractive to manufacturers wanting a lower risk entry point to the U.S. market.

On the other hand, USMCA may frustrate developing economies looking to build out manufacturing sectors focused on high margin, high skilled goods whose geographical location now puts them at a disadvantage to North America.

Source: Panjiva

Q: Any thoughts on whether “in-market, for-market” is likely to happen?

The in-market, for-market strategy has always been about the tradeoff between manufacturing costs and logistics costs. In the past where we’ve seen companies use this strategy has been in larger markets that are generally harder to enter, be it China, India, Brazil.

The combination of more aggressive U.S. trade policy and fears about international trade reliability in the face of another pandemic may make the combined North American market, reinforced by USMCA, more attractive to companies.

It is important to note that USMCA solidifies Mexico as a lower labor cost option for the U.S. market, despite the implementation of regulations tightening employment practices. That may carry some political risk if it appears that companies are avoiding U.S. reshoring to go to Mexico.

A good example of this are auto manufacturers who already use a combination of U.S. and Mexico production. General Motors faced political pushback after closing its plant in Lordstown, OH while Ford’s launch of the new Bronco shows a split production strategy, with the premium model being built in Wayne, MI and the downmarket Sport being produced in Hermosillo, Mexico.

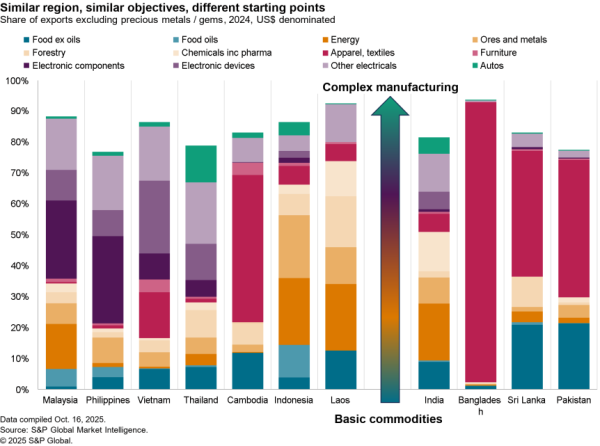

Q: Do you see India, Central Europe or Latin America benefitting from the trade war between the U.S. and China?

As flagged already, industrial supply chain choices are made on a mixture of cost and risk mitigation criteria. In theory then any location that offers a strong combination of both is a potential site for manufacturers relocating away from China.

Exporters from Central Europe, within the EU may suffer from risk issues related to deteriorating relations between the EU and U.S. flagged in Panjiva’s Q3 Outlook. As a counterpoint exporters from Latin America may be at an advantage given the push towards new trade deals with the U.S., particularly in the case of Brazil even if that isn’t likely to be completed until the end of the year. Many LatAm economies are still resource-export focused though so significant investments may be needed to expand manufacturing.

The scale of the Indian market, combined with the government’s aggressive “Make in India” tariff package has meant that it has been a target for manufacturers pursuing “in-market, for-market” investments. Yet, the government’s unwillingness to join the RCEP trade deal on current terms as well as ongoing border disagreements with China may make it less attractive as an environment for exporters.

Panjiva’s data shows exports from India in 2019 10.3% versus 2016. Meanwhile those from Vietnam and the Philippines, which have been popular “China+N” strategy destinations, have increased by 20.0% and 13.6% respectively.

Source: Panjiva