The U.S. and China have signed the long-awaited phase 1 trade deal, bringing to an end – or least a pause – a process of escalating tariffs and rhetoric running since Aug. 2017 (see appendix for a full review of that process).

What is the U.S. committing to?

The U.S. has previously committed to trimming list 4A tariffs applied under the section 301 process to 7.5% from 15.0%, which will take place from Feb. 14. Other than that the U.S. does not appear to make any concessions – or commitments on future tariff reductions – within the document. It’s perhaps not a surprise, therefore, that President Xi did not attend the signing ceremony.

Panjiva analysis shows the U.S. tariff reductions cover $120.2 billion of imports, or 41.2% of list 1-4A products. It remains to be seen whether the lower rate will make a difference to imports from China. List 3 imports which have a 25% tariff applied since May fell by 37.5% year over year in the three months to Nov. 30 while list 4A which was set at a 15% rate in September, fell by 26.4%.

Source: Panjiva

What’s China committing to?

From a policy perspective China’s commitments include: stronger protection of intellectual property including patent protection; an end to technology transfer requirements; restrictions on outbound investment in foreign technology; reduced non-tariff barriers to agricultural trade; improved financial services access including foreign ownerships; and currency control rules.

While the commitments on policy are arguably more substantive in terms of long-term relations between the two countries, it’s the purchasing commitments that have attracted the most attention and raise the biggest issues for enforcement (see below).

In terms of purchases the U.S. commitments amount to imports of $290 billion in 2020 and $328.6 billion in 2021. That would represent a 142.9% rise or $193.3 billion in 2021, Panjiva’s analysis of the 548 products covered shows.

Source: Panjiva

Looking in more detail, the manufactured products commitment comes to $83.6 billion of imports in 2020 and $95.5 billion in 2021. The latter represents a 88.4% rise versus 2017 or $44.8 billion of additional imports. The uplift would add 7.4% to current U.S. exports of those products ranging from industrial and electrical equipment through steel and chemicals.

One major challenge is that exports of semiconductors are included in the mix, whereas the U.S. wants to limit China’s technology purchases more broadly. Another is that aircraft orders or deliveries are counted – Boeing’s 737 Max remains grounded and China is trying to support the COMAC. More broadly though many of the manufactured goods relate to consumer goods where it’s not clear how a “Buy America” policy would work.

In agriculture there are commitments to $40 billion of purchases each year in 2021 with a stretch goal of $45 billion. The lower figure represents a 93.2% rise versus 2017 levels, or $19.5 billion of additional sales. Broadly speaking the increase is equivalent to 14.3% of U.S. agricultural exports more broadly. The easiest areas for redirection include cereals and meat, while soybeans represent the largest individual lever. It’s worth noting that the Chinese government will make purchases in line with market conditions and demand however.

Energy purchases are to reach $26.1 billion in 2020 then $41.6 billion in 2021, the latter of which would represent a 443% increase. As outlined in Panjiva’s 2020 Outlook this can be achieved through increased LNG and crude oil exports.

However, there may simply be a redirection of existing output – the growth required represents 37.0% of existing output with fungible commodities – and again market pricing will be used by the Chinese government.

Finally, services exports are to reach $68.8 billion and $81.1 billion in 2020 and 2021, representing growth of 44.8% or $25.1 billion versus 2018. If anything that may prove to be the most challenging area of delivery. While there will be an opening of equity ownership in financial services there’s still questions as to whether U.S. financial firms will be willing to engage in the time frame involved. Notably the commitment also includes cloud services where again the U.S. is looking to apply technological restrictions

Source: Panjiva

What’s the impact on supply chains?

The biggest issue though will be enforcement – the methods, thresholds and sanctions will be key to providing supply chain operators with the confidence or otherwise to resume normal business operations and investment.

The phase 1 document includes detailed procedures for dispute settlement including timing and attendees. However, it appears to say nothing about review periods – there’s a biannual ministerial meeting but month-to-month tracking isn’t ruled out – nor are there details of sanctions for non-delivery, though presumably these will include an increase in tariffs.

There will be a period of 30 to 45 days depending on the dispute for initial meetings to be held. Most worryingly though is that it appears either party can withdraw from the deal with a few as six days notice.

The first waymarker will be financial services commitments by Apr. 1, 2020 for securities ownership and insurance services.

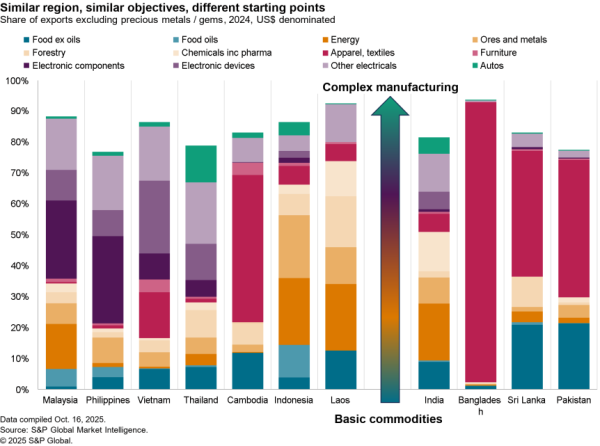

Firms have already been restructuring their supply chains between China and the U.S., particularly in consumer goods recently, and we’re likely to see more of the same. Panjiva data shows that U.S. imports of furniture from China fell to 44.4% of the total in the past 12 months from 49.6% in 2016. In apparel the ratio fell to 35.0% from 40.3%. As a counterpoint for electricals it has increased to 46.0%, showing complex supply chains can take longer to realign.

Chart compares U.S. imports of furniture from China versus total U.S. imports of apparel, electrical goods and furniture. Source: Panjiva

What’s next?

Phase 2 talks may initially start with heads of state meetings, though no formal dates have been set. Talks will need to focus on deeper economic policy issues – in particular support for technological development and subsidies for major industries. Those have been conspicuous by their absence in the phase 1 deal.

There are already four potential stumbling blocks, however. The U.S. State Department has already expressed concerns about China’s new cryptography law which requires access by the Chinese government to Chinese firms data held in third countries.

There are also emerging export restrictions on high technology products on the way from the Commerce Department which have already applied restrictions to AI related software and products.

The U.S. Treasury is also tightening the rules for investment in sensitive real estate and technology assets by state-controlled firms. There’s also signs of attempted micro-management of technology spending, exemplified by Huawei where the administration is limiting both purchases from and sales to the Chinese telecoms operators, Reuters reports. Fifth, the U.S. Department of Defense has called on TSMC to move semiconductor manufacturing to the U.S. if it wants to retain access to military programs.

So far actually there’s been an acceleration in Chinese imports of semiconductors and circuits from the U.S. of 14.6% year over year in the three months to Nov. 30 and by 32.3% in the past 12 months to reach 18.8 of the total.

At the same time have seen more lackluster growth in exports to Mexico and Canada, which represented 25.5% of the total, with growth of just 3.8% in the past three months. For semiconductor manufacturing equipment there has been a longer term decline in exports to China of 9.7% in the past 12 months though a 34.7% bounce in the past three months indicates signs of stockpiling.

Source: Panjiva

Are there external risks to the deal?

Compliance with World Trade Organization rules may be suspect given the Chinese government is explicitly preferring one country over another in terms of import rules. That may be a moot point though given the deadlock in the WTO’s dispute settlement process which will likely last through the next two years.

The bigger issue may be the U.S. elections, with Democrats attempting to either outflank President Trump in being “tough on China” while also pushing differentiated but still hawkish trade policies.

Senator Warren has already published a hawkish trade plan that would appear to prohibit doing a wider trade deal with Chinastating “we’ve let China get away with the suppression of pay and labor rights, poor environmental protections, and years of currency manipulation“. Similarly, Senator Biden has been critical of the phase 1 deal stating that “China is the big winner” and that the deal “won’t actually resolve” issues including subsidies, state-owned enterprise support and “other predatory practices“, Bloomberg reports.

Similarly, Senator Sanders has been consistently hawkish regarding trade more broadly from a labor perspective and voted against allowing China to join WTO in the first place.

Trade with China, and the impact of lower exports to China due to the trade war so far, may become an issue during the elections at the state level. Among early primary states exports to China from New Hampshire fell by 31.2% in the 12 months to Nov. 30 versus 2017 while those from Nevada have fallen by 36.1%.

Source: Panjiva

Appendix – The Trade War Show, The Story So Far

Aug. 2017 to Mar. 2018 – Building rhetoric

Aug. 21 2017 – The U.S. Trade Representative launched a section 301 trade review focusing on China’s intellectual property and technology transfer policies at the behest of President Trump, whose Executive Order also focused on the width of the U.S. trade deficit versus China. Panjiva data for U.S. imports and exports shows that the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with had reached $355.6 billion in the 12 months to Jul. 31 2017, representing 46.5% of the total U.S. trade deficit at that stage. Winding the clock forward, by Jun. 2019 the deficit reached $405.4 billion after peaking at $423.6 billion in the 12 months to Jan. 2019.

Nov. 9 2017 – A summit meeting between President Trump and President Xi included the signing of $253 billion worth of commercial deals – including investments and purchases – spread over several years. That provides the first signs that commercial deals as much as policy deals matter to the Trump administration.

Dec. 19 2017 – The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy marks China as a “strategic competitor“, moving the section 301 process outside realm of trade policy and into broader geopolitical rivalry between the two countries. Arguably that undermines the likelihood of an eventual conclusion, rather than just a cessation, of hostilities.

Jan. 17 2018 – In a contentious phone call President Trump refers to the trade deficit as being “not sustainable” while President Xi calls for comprehensive talks “at proper time”.

Feb. 7 2018 – China considered launching an antidumping investigation into U.S. soybean exports, joining an earlier probe into sorghum imports, demonstrating a willingness to leverage the agricultural sector in negotiations.

Mar. 9 2018 – The implementation of national security-related tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum by the U.S. under the section 232 process led China to apply retaliatory duties on soybeans that were worth $12.4 billion in 2017, Panjiva data shows. Those have fallen to $2.5 billion in the 12 months to Apr. 30. Increase exports to other countries have meant U.S. exports in total fell 22.5% in the 12 months to Apr. 30 versus 2017, though farmers are currently also struggling with excess rainfall and river-barge closures too.

Mar. 2018 to Jun. 2018 – Opening salvos

Mar. 13 2018 – The U.S. government called on the Chinese government to find $100 billion of purchases to cut the U.S. trade deficit. That indicated the potential to use a wide-ranging purchase agreement by Chinese state-owned enterprises as an off-ramp from tariffs.

Mar. 26 2018 – The USTR announced the result of its section 301 review with recommendations that tariffs of 25% be applied to $50 billion of Chinese exports in two phases in July and August. The formal list of products covering 1,333 items focused on industrial supply chains was announced on Apr. 4.

Apr. 5 2018 – China responded with its own list of $50 billion worth of products for retaliatory duties at a 25% rate, focused on 106 tariff categories with a focus on commodities, aerospace and autos.

Apr. 6 2018 – President Trump ordered the USTR to consider which products to apply counter-retaliatory duties to, initially covering $100 billion and then raised to $200 billion across a range of non-consumer products.

May 7 2018 – A summit meeting including Secretary Mnuchin, Ambassador Lighthizer, and Vice Premier Liu He included U.S. demands for a $200 billion reduction in the trade deficit alongside Chinese calls for a relaxation of rules on exports of high-tech products to China from the U.S.

May 18 2018 – Following the summit the Chinese investigation of sorghum dumping was cancelled, though they continue to be covered by the initial list of $50 billion of products under section 301 retaliation.

Jun. 4 2018 – Meetings between Vice Premier Liu and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross reveal plans for multi-year contracts for purchases in agriculture as part of a long-term settlement in the trade war.

Jun. 15 2018 – President Trump approved the $50 billion tariff package which included different products from the original list, including construction equipment. As at Apr. 30 imports of those products had fallen by 28.4% year over year, Panjiva analysis shows. The subsequent tariff group (see below) of $200 billion had dropped by 22.0% over the same period.

Jun. 2018 to Nov. 2018 – Digging in deeper

Jun. 18 2018 – As expected China launched tariffs on its own list of $50 billion of products, focused on agriculture and energy. At the same time the U.S. repeated its threat to add a further $200 billion of products to the duty list.

Jul. 6 2018 – First set of duties go into place at a rate of 25% on the initial list of $34 billion out of the $50 billion of targets on both sides.

Jul. 11 2018 – The USTR specifies a list of $200 billion of products to which a rate of 10% will be applied, including 6,031 product lines which mostly avoid consumer goods.

Aug. 5 2018 – China reacts to the $200 billion list with its own target list of $60 billion of imports from the U.S. with duties to be applied at between 5% and 25%. The list covers 56% of all products though the rates eventually applied were capped at 10%.

Aug. 22 2018 – The U.S. and China hold the first round of talks to resolve the trade conflict, though little is declared between an agreement to have comprehensive discussions regarding both countries trade policies.

Sept. 17 2018 – President Trump orders the application of 10% duties on $200 billion of imports from China from Sept. 24, with the rate set to increase to 25% in January.

Sept. 19 2018 – The Chinese government applies its counter-counter retaliation riposte and also cancels previously planned negotiations.

Nov. 2 2018 – The procedure for companies to request hardship-related exemptions from the initial 25% duty round from July yields 8,241 applications. That eventually rose to 13,750 requests with 24.3% of decisions leading to exemptions as outlined in Panjiva’s research of Jun. 4.

Dec. 2018 to Apr. 2019 – A fragile truce

Dec. 3 2018 – President Xi and President Trump agreed a 90 day cessation of tariff increases while a new round of negotiations begin. China also commits to increased purchases of energy products including LNG and oil.

Jan. 10 2019 – The first round of talks confirm a wide range of economic policies will be covered, though the U.S. also remained focused on the trade deficit, announcing China will “purchase a substantial amount of agricultural, energy and manufactured goods” and that any agreement will include “ongoing verification“.

Mar. 4 2019 – President Trump called directly for China to “immediately remove” all its tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports shortly before a summit meeting with President Xi, perhaps indicating the pressure from farmers on the Trump administration.

Apr. 1 2019 – Talks continued beyond the 90 day deadline set in January. The Chinese government suspended duties on imports of U.S. autos, possibly as a gesture of goodwill. Exports of cars and light trucks from the U.S. to China have nonetheless fallen 20.5% year over year in the three months to Apr. 30, including a 53.7% slump in the month of April. The sector will come back into focus later in the year as a decision in the section 232 review of the autos industry is due by November.

Apr. 18 2019 – Two rounds of negotiations were scheduled for Apr. 29 and May 8 with a view to reaching a conclusion in negotiations.

May 2019 to June 2019- Detente turns ugly, gears of war enhanced

May 7 2019 – President Trump commits to a May 10 rise in list 3 tariffs to 25% from 10% as negotiations were going “too slowly” and starts a process to review tariffs on all remaining Chinese exports.

May 10 2019 – China unsurprisingly reacts with an increase in duties on list 3 products as well as threatening “necessary countermeasures”.

May 16 2019 – President Trump repeatedly refers to tariffs being paid by China, when tariffs are actually paid by importers. However, there are clear signs of import price reductions suggesting a degree of burden sharing with exporters. Customers may end up paying the cost though with a wide cross-section of retailers threatening to utilize price increases to pass through tariffs to customers.

May 22 2019 – Following a visit by President Xi to a rare earth processing facility, speculation rises that China will apply export restrictions designed to inhibit U.S. high tech manufacturing. Details of a “national technological security” investigation follow in June. The Chinese government also moved to provide tax breaks to its semiconductor industry.

May 23 2019 – Similarly the U.S. threatens to restrict sales of U.S. technology components to Chinese companies ranging from Huawei to Hikvision.

Jun. 2 2019 – The Chinese government plans to implement an “unreliable entities” list of companies that, among other things, “deviate from the spirit of contracts”. The tool may provide a root for direct intervention against U.S. firms – FedEx appears to be the first in the crosshairs.

Jun. 10 2019 – President Trump threatened to accelerate tariff increases if a bilateral meeting isn’t held with President Xi at the forthcoming G20 meeting from Jun. 28. In the meantime China’s exports to the U.S. have fallen by less than vice versa in May with the result of further increases in the U.S. trade deficit with China. Indeed, as of May 31 China’s 12 month trailing trade surplus with the U.S. reached $329.8 billion, or 29.9% higher than Dec. 2016.

July 2019 – Aug. 18 2019 – Trade peace becomes a wider geopolitical conflict

Jul. 1 2019 – President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping agreed to restart negotiations towards a wide-ranging trade deal. The U.S. will be “holding on (applying further) tariffs” while China is “going to buy farm products” according to President Trump. In many regards that’s the same arrangement reached in May 2017 and Dec. 2018, though detailed negotiations on economic progress have made progress since then. The two Presidents also agreed to relax restrictions relating to component exports to Huawei, raising the profile of technology in the talks once more.

Jul. 10 2019 – The U.S. government approved a $2.22 billion arms sale to Taiwan including tanks and missiles. Unsurprisingly the move drew criticism from the Chinese government which has threatened sanctions against U.S. military equipment companies involved in a related deal for the F-16 fighter jet, according to the BBC.

Jul. 29 2019 – The Chinese government reportedly started approvals for shipments of corn, cotton, port and sorghum, potentially worth $1.52 billion in the following six months based on previous seasonal shipments in the six months to Oct. 31. China also announced plans for “high-level economic and trade consultations in the U.S. in September” according to Xinhua.

Aug. 2 2019 – Despite plans for talks, President Trump announced tariffs would be applied to all imports from China where tariffs had not already been applied – though some goods were subsequently excluded – at a rate of 10% from Sept. 1. The biggest products not yet covered are all in the consumer sector and include: smartphones where Panjiva data shows imports were $43.2 billion in 2018, representing 81.8% of total imports; apparel and footwear worth $42.1 billion, representing 37.6% of the total; laptop PCs worth $37.5 billion, equivalent to 94.4% of the total; toys worth $11.9 billion which is 97.6% of the total; and videogame consoles worth $5.4 billion, representing 97.6% of the total.

Aug. 6, 2019 – The Chinese yuan/dollar exchange rate fell 2.2% between Aug. 1 and Aug. 6 as the Chinese government allowed the collar rate to slip. That led to U.S. Treasury Department designating China as a currency manipulator “at the behest of the President”. The decline may be an attempt by the Chinese to offset the latest tariff threat from the U.S. government.

Aug. 13 2019 – The Trump administration decided to split the implementation of list 4 tariffs into two parts. List 4A would have tariffs applied from Sept. 1 and cover $109 billion of imports and include apparel worth $38.8 billion and TVs / monitors worth $8.6 billion. List 4B, worth $154.8 billion, will have tariffs applied from Dec. 1 and cover phones, laptops, toys and apparel. The delay was likely designed to (a) reduce the impact on American consumers and (b) provide a degree of de-escalation.

Aug. 18 2019 – Geopolitics became further embroiled with the trade war – not only had China linked American arms sales to Taiwan, President Trump stated that “Hong Kong (protests) worked out in a very humanitarian fashion … would be very good for the trade deal” according to Reuters. The latter has come on top of potential legislation from the U.S. Senate that could lead to Hong Kong losing its special customs status.

Aug. 23 2019 to Oct. 11 2019 – This time it was different

Aug. 23 2019 – The Chinese government announced additional tariffs of between 5% and 10% on 5,078 products imported from the U.S. in two phases as a retaliation to the U.S. move of Aug. 13. The rates will be applied on Sept. 1 (equivalent to list 4A) and Dec. 15 (list 4B). The Chinese government also threatened to launch its “unreliable entities” list according to CNBC as well as revoking the earlier reduction in automotive duties.

Aug. 23 2019 – The U.S. Trade Representative orders an across-the-board increase in tariffs of 5% points on existing section 301 duties as well as a hike in planned tariffs to 15% from 10%. President Trump issued an “order” to U.S. companies to withdraw activities from China, citing the potential to utilize the Emergency Economic Powers Act. The implementation of that move could be limited – for example to the investment policy of the U.S. state pension funds according to the Financial Times – and was ultimately not enforced.

Sep. 1 2019 – The imposition of list 4A tariffs led a series of retailers including Best Buy to announced price increases to pass through tariffs to customers. Target took a different strategy however, insisting that its suppliers not pass through tariff-related price increases.

Sept. 5 2019 – The Chinese government announced the sub-ministerial talks will be held in mid-September with a view to holding ministerial meetings in October with a view to de-escalating planned tariff increases.

Sept. 11 2019 – The Chinese government subsequently allowed exemptions from tariffs 16 products imported from the U.S., potential to help negotiations. Products included are led by agricultural products as well as lubricants and medical devices worth an aggregate $870 million of imports in the 12 months to Jul. 31. In response the U.S. government delayed the planned tariff increase to 15% by two weeks to Oct. 15 to allow talks to proceed after the lunar new year.

Sept. 20 2019 – The September round of talks yielded a relatively bland commitment to continue negotiations. Furthermore President Trump indicated that a partial deal wouldn’t be of interest. In response Chinese official cancelled a planned visit to U.S. farming states, which could have been the catalyst for an announcement. At least the mid-October talks remained on schedule.

Oct. 11 onwards – Phase 1 launched

Oct. 11 2019 – The U.S. and China announced a framework “ phase 1” trade deal, with a further five weeks of talks planned to formulate a signable deal by the time of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC) from Nov. 16. The deal focuses on postponing the planned Oct. 15 tariff increase alongside Chinese commitments to $40 billion to $50 billion of agricultural purchases. By comparison Chinese imports of those products from the U.S. was $8.2 billion in the 12 months to Aug. 31 with a prior peak of $20 billion in the 12 months to Jun. 30, 2017. A second phase of talks is scheduled to begin once the phase 1 deal is signed.

Oct. 29 2019 – The APEC summit was cancelled due to ongoing civil unrest in Chile with no alternative venue or date set for the next meeting between President Xi and President Trump to sign the phase 1 deal.

Nov. 6 2019 – U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross indicated the phase 1 deal could include LNG as well as agricultural products. U.S. LNG exports had already been surging despite the trade war, with a 65.3% rise in September compared to a year earlier after the opening of another new export terminal in Texas.

Nov. 7 2019 – China’s Commerce Ministry indicated that the phase 1 deal could include the roll-back of tariffs by the U.S., as well as a pause in increasing tariffs in mid-December. A deal is now set to be signed by President Trump and President Xi ahead of the planned tariff increase on Dec. 15.

Nov. 13 2019 – President Trump’s speech at the Economic Club of New York identified the potential to still increase tariffs if the details of a phase 1 deal couldn’t be completed, and that work on the “Reciprocal Tariff Act” could continue.

Dec. 15 2019 – As expected, the broad-brush terms of the phase 1 deal were released at the last minute. China will commit to around $200 billion of additional purchases from the U.S. in 2020 and 2021 versus 2017, the U.S. will halve list 4A duties and both sides will put in place enforcement and trade policy adaptations. Much of the rest of the year was spent focused on translating the initial deal into mutually agreed, translated texts.

Update (Jan. 21, 2020): Tables of purchasing objectives updated for details from trade deal documentation.